Legal beginnings

Tai Sing v. Maguire

Tai Sing challenged the right of the local tax collector in Victoria, B.C., to seize and sell his property under the Chinese Tax Act, which had been created by the B.C. Legislative Assembly in August, 1878, to enumerate and tax all Chinese living in the province.

The provincial law had required among other things that “every Chinese person over twelve years of age shall take out a license every three months, for which he shall pay the sum of ten dollars, in advance, unto and to the use of Her majesty, Her heirs and successors.”

The law further stipulated that employers of Chinese could be held liable if employees did not pay the tax, and that their property and other assets could be seized. Additionally, Chinese persons in violation of the law could be forced into service on public works at a rate of fifty cents per day until the tax was paid, and they could also be charged more fees to cover their food, guard’s wages and for the use of tools while working to pay their debt.

Tai Sing challenged the constitutionality of the Chinese Tax Act and B.C. Supreme Court Justice J. Hamilton Gray held that the law was beyond the power – ultra vires – of the provincial assembly, and further asserted that only the federal government had the power to make laws in regards to aliens, trade and commerce and treaty making. “The present Act is entirely beyond the powers of the local legislature, and is therefore, unconstitutional and void,” Justice Gray wrote in his decision.

The B.C. Chinese Tax Act (1878) was struck down with Justice Gray’s ruling, but it entirely failed to address the discriminatory treatment of the Chinese under the law. Significantly, it left open the door to federal law being used to discriminate against the Chinese – which occurred seven years later with the first federally mandated head tax on Chinese.

R. v. Wing Chong

The B.C. Legislative Assembly remained undeterred by its first attempt to limit the Chinese, enacting myriad other laws to disadvantage them politically, economically and legally.

In 1884, the B.C. legislature passed into law the Chinese Regulation Act, creating an annual tax of $10 on every Chinese person over the age of 14, defining the target of the legislation as “any native of the Chinese Empire or its dependencies not born of British parents, and shall include any person of the Chinese race.”

The Regulation Act went further than imposing a racially discriminatory tax; it also prohibited issuing licenses to Chinese for a variety of occupations, prohibited the exhumation of Chinese bodies, ostensibly for their return to China, and imposed size restrictions on accommodations inhabited by Chinese. Also contained within the Act was a higher levy on Chinese applying for a “free miner’s certificate,” set at $15 while everyone else paid an annual fee of $5.

The B.C. Chinese Regulation Act (1884) also was challenged in court within a year of its passing.

The case, R. v. Wing Chong (1885), was brought by a Chinese who was fined $20 for failing to pay the annual tax. Chong argued against the constitutionality of the Act, on grounds that it violated federal jurisdiction on the rights of aliens and trade and commerce; it was also argued that the Act introduced an unequal taxation scheme. Chong further argued that the intent of the law was not to raise revenue or for police purposes, but rather to prevent more Chinese immigration to British Columbia and to encourage those already resident to leave.

The B.C. attorney general, however, argued that the Regulation Act was purely about taxation and therefore within the rights of the province. The court decided that the Regulation Act was ultra vires the province’s power to enact legislation and it was declared unconstitutional and rescinded.

Setting precedence

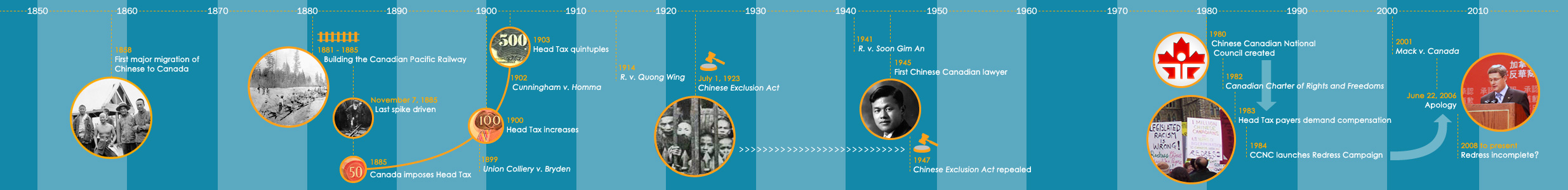

Other cases, like Union Colliery v. Bryden (1899) in which a company shareholder sought to ban Chinese from certain work in B.C.’s coal mines, and Cunningham v. Homma (1901) where British Columbia’s electoral franchise laws were challenged, set legal precedence that would affect the status of Chinese in Canada and their standing before the courts for decades.

Judiciary and Privy Council decisions on these two cases further defined jurisdiction in the area of “aliens or naturalized subjects,” particularly with regard to rights attached to either status.

Discriminatory laws were passed in jurisdictions across Canada against the Chinese. In many cases, the Chinese Canadian community tried its best under the circumstances and with their reduced rights and legal status to challenge the law itself.

Please refer to the list of key Court Cases for further information.