Perpetual foreigners

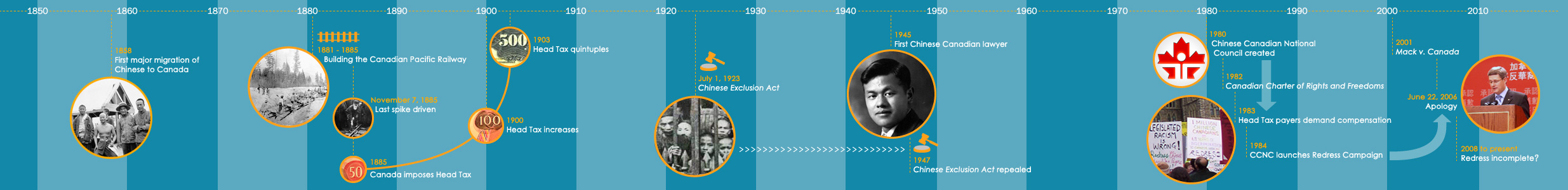

Attitudes towards the Chinese varied throughout Canada, but by 1885 when the transcontinental Canadian Pacific Railway was completed with Chinese help, opposition – especially from British Columbia – began to colour views against their presence in the relatively young country.

In a speech in the House of Commons, on May 4, 1885, Prime Minister John A. Macdonald argued for the exclusion of the Chinese from Canada, despite having earlier supported their presence during the building of the CPR.

“When the Chinaman comes here he intends to return to his own country; he does not bring his family with him; he is a stranger, a sojourner in a strange land, for his own purposes for a while; he has no common interest with us,” Macdonald intoned before his fellow parliamentarians. “A Chinamen gives us his labour and gets his money, but that money does not fructify in Canada; he does not invest it here, but takes it with him and returns to China . . . he has no British instincts or British feelings or aspirations, and therefore ought not to have a vote.”

Macdonald’s comment, and misrepresentation of the intent of many Chinese immigrants to stay and settle in Canada, coincided with national debate on the “Chinese question” and the ongoing Royal Commission on Chinese Immigration (1885).

While much of the testimony recorded by commissioners Justice John Hamilton Gray and J. A. Chapleau focused on racialization of the Chinese and their popular characterization as “perpetual foreigners,” the commissioners also interviewed the Chinese consul-general in San Francisco, representing the Chinese Imperial court.

The commissioners also decided to embark on a fact-finding mission to California to study the American experience with the Chinese, with the full knowledge that the United States had passed its own Chinese Exclusion Act in 1882.

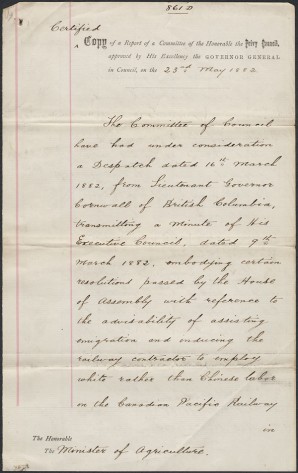

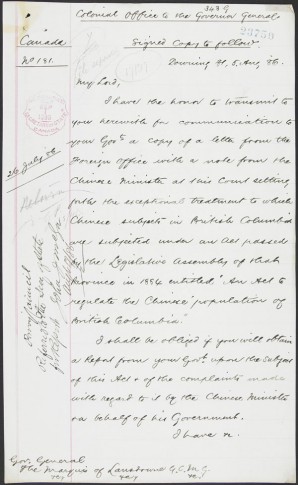

Clerk of Privy Council - Refers letter of Colonial Office to Governor General re treatment of Chinese subjects in British Columbia.

Chinese perspective

During the mission, officials consulted Consul-General Huang Tsun Hsien in San Francisco, rather than conduct their inquiry through the Privy Council and Chinese legation in London, which would have taken considerably more time. Asked to comment after he was interviewed, Huang made the following statement:

“Q. Have you any further information to impart?—A. I would like to say this: That it is charged that the Chinese do not emigrate to foreign countries to remain, but only to earn a sum of money and return to their homes in China. It is only about thirty years since our people commenced emigrating to other lands . . . You must recollect that the Chinese immigrant coming to this country is denied all the rights and privileges extended to others in the way of citizenship; the laws compel them to remain aliens. I know a great many Chinese will be glad to remain here permanently with their families, if they are allowed to be naturalized and can enjoy privileges and rights.”

Huang’s comments have nearly been forgotten in Canada’s official history, but they are important and stood as a warning against the subsequent decades of official racism against the Chinese in Canada that was largely supported through discriminatory legislation.