CCNC takes the case

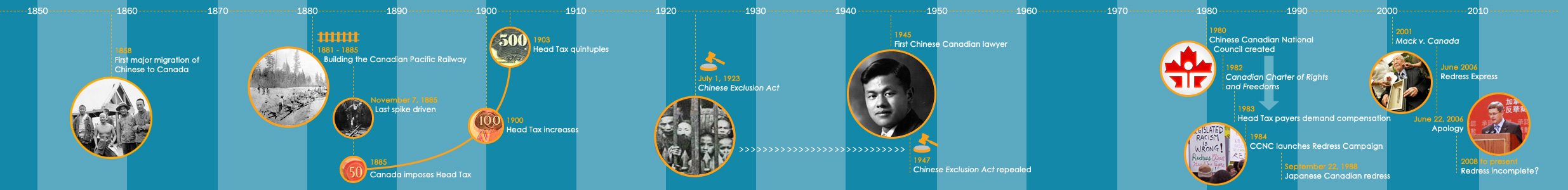

In 1979, Chinese Canadians across the country united to protest the irresponsible journalism of CTV’s W5 program entitled “Campus Giveaway”. As a result, CTV publicly apologized for the racist overtones and inaccuracies of that particular episode. Participants against W5 from cities across Canada assembled and held a conference in Toronto. Out of that meeting, the Chinese Canadian National Council (CCNC) was formed in order to promote the equality rights for all Chinese Canadians.

CCNC made the head tax apology and redress a priority for the organization in 1987, in preparation for a federal election the following year. Over 4,000 Head Tax payers, spouses and descendants entrusted CCNC with representing them in seeking an apology and financial redress. Significantly, CCNC worked with the National Association of Japanese Canadians, which negotiated a settlement with the Canadian Government in 1988 over the internment of Japanese Canadians during World War II. Among other things, the settlement contained a government acknowledgment of the injustice done to Japanese Canadians, a $21,000 payment to each survivor, $12 million to the Japanese Canadian community and $24 million to set up the Canadian Race Relations Foundation.

A settlement remained elusive for Chinese Canadians. CCNC struggled through various governments to keep politicians apprised of the issue – holding numerous community meetings, gathering support from other groups and prominent Canadians, increasing media awareness and conducting research, and meeting with various Multiculturalism Ministers on the issue, etc. But meanwhile the community was losing its surviving head tax payers and their spouses.

The first few years of the 1990s saw the focus of the redress campaign shift to the B.C. Coalition of Head Tax Payers, Spouses and Descendants. This grassroots group signed up over 1,500 new Head Tax claimants in support of CCNC and its redress efforts. A number of huge community meetings were held to keep the pressure on the Government and the spotlight on the redress campaign.

Before the 1993 federal election, former Prime Minister Mulroney tried to settle several ethno-cultural communities’ redress claims by offering individual medallions, a museum wing and other collective measures. This was rejected outright by the Chinese, Italian and Ukrainian Canadian national groups.

In December, 1994, then Minister of Multiculturalism Sheila Finestone announced in Parliament that the government would not provide redress for the head tax and other historical injustices against other communities. Despite this setback, redress supporters continued to raise the issue whenever they could, including a submission to the United Nations Human Rights Commission. Another decade passed before the community made any significant progress.

Case goes to Supreme Court

As the political process stalled, CCNC and its allies, notably the Metro Toronto Chinese & Southeast Legal Clinic, turned to the Canadian courts for justice. In 1999, Plaintiffs Mr. Mack, Quen Ying Lee and her son Yew Lee filed a class action law suit, hinging part of their case on guarantees of equality before the law enshrined in Section 15 of the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms. In a decision released in 2001, Ontario Superior Court Justice Cumming found that there “was no reasonable cause of action” and dismissed the case. The judge’s reasoning was that the Chinese Immigration Act (1923) and it amendments, which had created the head tax and exclusion laws, were repealed in 1947. Judge Cumming ruled, however, that the Charter could not be applied retroactively or retrospectively. The Ontario Court of Appeal, on Sept. 13, 2002, upheld Justice Cumming’s ruling.

Canada’s law courts failed to deliver justice to Canadians of Chinese descent for the head tax and the Exclusion Act for the last time on November 18, 2002, when the Supreme Court of Canada turned down a request by Mr. Shack Jang Mack for leave to appeal the class action against the Government of Canada.

Consistent with its general practice, the country’s highest court did not give a reason for dismissing Mack v. Canada (2002); nor did it have any words for Mr. Mack, the lead plaintiff in the case, who had passed away just weeks before the dismissal – without ever seeing justice done.