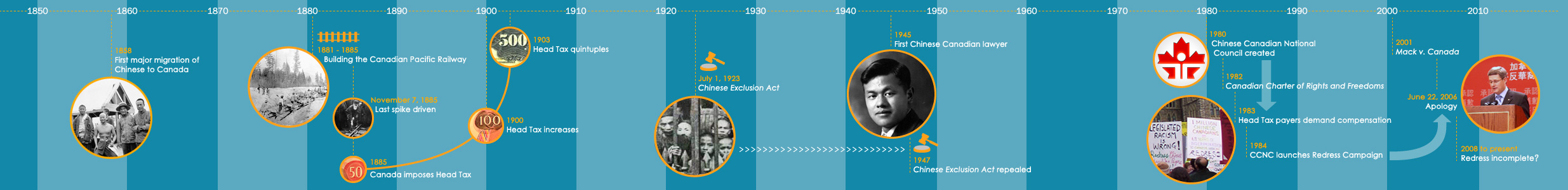

Anti-Chinese legislation

From Confederation in 1867, the federal and provincial governments sought to restrict settlement in the new country of Canada to subjects of the British Crown and other preferred classes of immigrants. For those classes of people who were not deemed favorable to settle the largely undeveloped lands east of Central Canada, and stretching to the West coast, economic disincentives – often empowered by legislation – were put up to discourage them.

Disenfranchisement and exclusion from the political and legal processes were also used against First Nations, Chinese and other peoples of Asian descent.

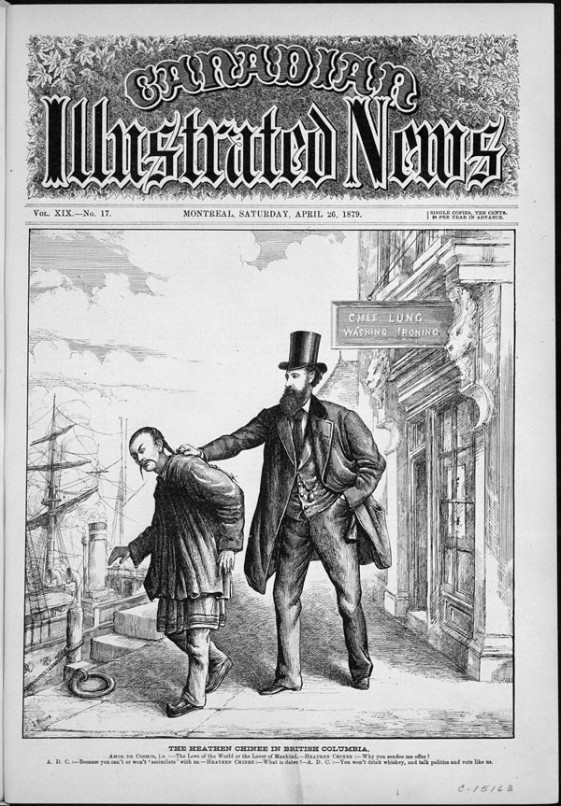

A cartoon from the Canadian Illustrated News depicting Amor de Cosmos telling a Chinese immigrant to leave British Columbia because he refuses to assimilate with the rest of the province

Racial inequity was a reality in early Canada.

Prevailing societal values, defined by the dominant class and largely regarded as British or European at the time, underscored the legislative process as it was developed and adapted to the Canadian system of federalism.

The discussion in Parliament in the months before Canada imposed its first discriminatory law targeting a single race of people, when lawmakers wrote up policy and legislation to create the first head tax of $50 on all Chinese immigrants, is indicative of the social order at the time.

Jurisdictional debate

Where the Chinese were concerned, policy and legislation in early Canada were broken down along racial lines. Any arguments that appeared to favour the Chinese, or that would have upheld any legal rights for them, were usually the result of jurisdictional push-and-pull discourse between the federal and provincial governments. A similar debate at the provincial level often led to municipal laws that were put in place to limit the Chinese, in political, legal or economic activities.

Jurisdictional issues were at the heart of many judgments on statutes involving Chinese, either directly as litigants or indirectly as those affected by many of the laws created in British Columbia to disadvantage them. Application of the principle that only the federal government could rule on matters concerning aliens, trade and commerce as well as treaty making also affected areas of law and policy that determined the status of Chinese in early Canada.

Immigration covered naturalization and rights of residency, while a separate set of laws dealt with electoral franchise, or the right to vote, and participate in organizations and government. Trade and commerce covered hundreds of laws enacted by Canadian municipalities and provinces to restrict Chinese activity and participation in the economy. Citizenship as a development in Canadian law was not formally established until much later, when Canada emerged from the Second World War.

Key court cases, identified in Road to Justice, illustrate the use of the law to limit or otherwise restrict the activities and control the lives of people of Chinese descent in Canada.