No more Chinese!

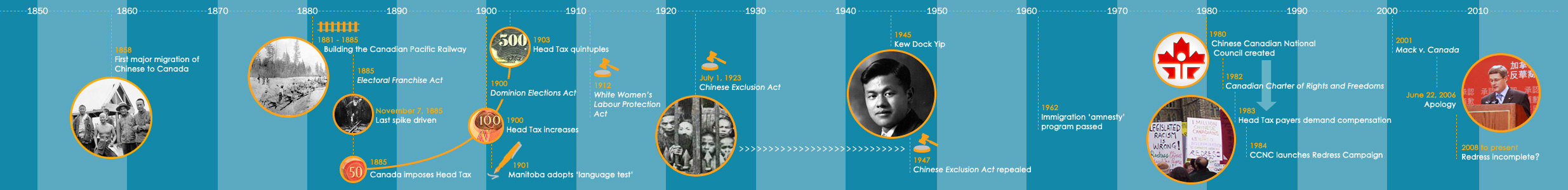

After World War I, the federal government replaced its discriminatory head tax on Chinese with a total prohibition on Chinese immigration to Canada.

The Chinese Immigration Act (1923) – also popularly known as the Chinese Exclusion Act – received assent on June 30, 1923. The next day, as other Canadians celebrated Dominion Day, Chinese Canadians marked what became known as “Humiliation Day.”

There were few exemptions to the ban, but diplomats, Canadian-born Chinese, merchants and students studying at certain institutions could still travel to and from Canada with the correct documents.

For Chinese Canadians, the two-year limit on travel away from the country still existed, but the penalty for not returning on time was even harsher: the additional $500 fee was replaced with a prohibition on returning to Canada.

The Exclusion Act also created difficulties for Canadian-born and naturalized Chinese. Section 18 of the law stipulated that every person of Chinese origin or descent in Canada, irrespective of allegiance or citizenship, was required to register with the authorities and to obtain an identity certificate.

Still, at least one Chinese Canadian fought in court to retain his rights.

Chinese beleaguered

Beyond losing all political rights through being disenfranchised, both provincially and federally, by having undue financial burdens placed on individuals, families and communities by the accumulated debt of the head taxes, the Exclusion Act seemed to erase all hope that any Chinese would ever be able to reunite with and raise their families in Canada.

The Chinese Exclusion Act was in force for 24 years, lasting through World War II. Canada’s discriminatory immigration law and resultant policies worked to limit the number of new arrivals from China, and it’s believed that only 44 Chinese were able to immigrate here legally between 1923 and 1947, when the Act was repealed.

Repealing the Act on paper was easy enough for the government, but for the many Chinese Canadians who endured the exclusion years, reconciling this part of theirs and Canada’s history would take generations.

After the Exclusion Act was repealed, restrictions on Chinese immigration continued, limiting entrance to only spouse and children of Canadian citizens and permanent residents of Chinese descent. About 11,000 Chinese came to Canada illegally as “paper sons”. In 1960, the “Chinese Adjustment Statement Program” was established to provide an amnesty to all the “paper sons”. It is believed that Douglas Jung, the first Chinese Canadian elected as a Member of Parliament in 1957 played a role in pushing for the amnesty.