By Winnie Ng

December 21, 2020

This article was first published on Our Times.

Chinese farmers, miners and loggers worked in BC decades before work on the railroad began. Here, loggers are seen with a steam donkey, used to haul logs. PHOTOGRAPH (DETAIL): VANCOUVER PUBLIC LIBRARY/VPL 78316

2019 marked the centennial of the Winnipeg General Strike, a milestone in the history of the Canadian labour movement. With deep gratitude, we salute these labour pioneers who did the heavy lifting and ground clearing for future generations of trade unionists. We continue to walk the path inspired by their legacy.

In exploring the wealth of recorded working-class history in Canada, I can never help asking whose stories are missing. Who are the people we consider ‘workers’ historically? Or more precisely, who were the ones excluded by organized labour then?

This is when my own digging started. I stumbled on the fact that in April 1919, a month prior to the Winnipeg General Strike, close to 2,000 Asian shingle workers organized a historic strike in British Columbia’s Lower Mainland to resist a discriminatory 10-per-cent wage reduction. The strike lasted for 40 days.

But what was the historical context? How did these workers muster such courage, tenacity, and probably, what seemed to many, the audacity to strike? How did these workers organize and build such a cohesive force?

With these questions, I began my excavation project, to bring to light some long-buried labour struggles that few historians have written about. It is an act of reclaiming the space, centred on the narratives of many early labour pioneers who were deemed others, whose voices and activism were dismissed; and whose struggles have yet to be embraced and celebrated by the labour movement as a whole.

The potential scope and depth of the project are immense, the work akin to a treasure hunt. I have focused my search primarily on the early labour struggles within the Chinese Canadian community. Exploring Chinese-language source materials is especially exciting — both scholarly work and community publications including the longest-running Chinese Canadian daily newspaper, the Chinese Times (Tai Hon Kong Bo), which served the Vancouver community from 1914 to 1992.

This excavation project is, above all, an exercise to dispel stereotypes of Chinese people as docile strike-breakers. In the stories below, it is clear that the early struggles of Chinese Canadian workers were about dignity and fairness. Their militancy and resistance were motivated by rage over overt and systemic racism, over the denial of their rights, and over their exploitation as workers on the basis of race and class.

With this article, I want to invite labour activists in Indigenous, Asian, Black and other racialized communities in Canada to join the excavation project and add richness to the fabric of Canadian labour history.

It’s time to share these untold tales of resistance for generations of labour activists to come.

_______________________________________________________

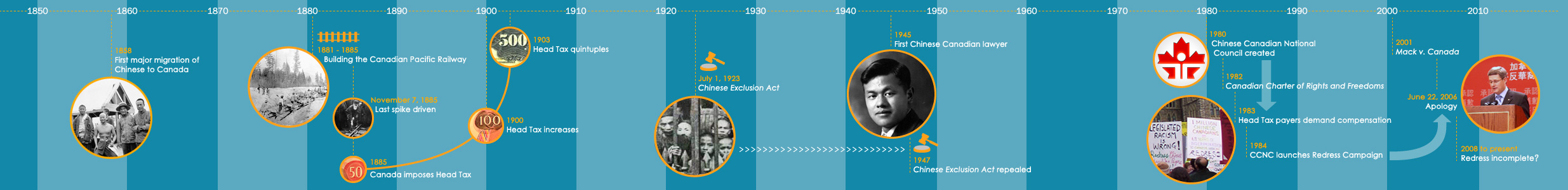

The Historical Context

Between 1881 and 1884, contractors brought an estimated 17,000 Chinese workers in from the southern coast of China as indentured labourers to build the Canadian Pacific Railway. As soon as the railroad was done, the government enacted anti-Chinese laws. Billed as “an Act to restrict and regulate Chinese immigration to Canada,” the Chinese Immigration Act of 1885 imposed a head tax of $50 on all Chinese, with the exception of diplomats, merchants, “men of science,” and students. That sum was equivalent to 50 days’ pay for a Chinese railroad construction worker, and amounts to $1,340 in 2020 dollars.

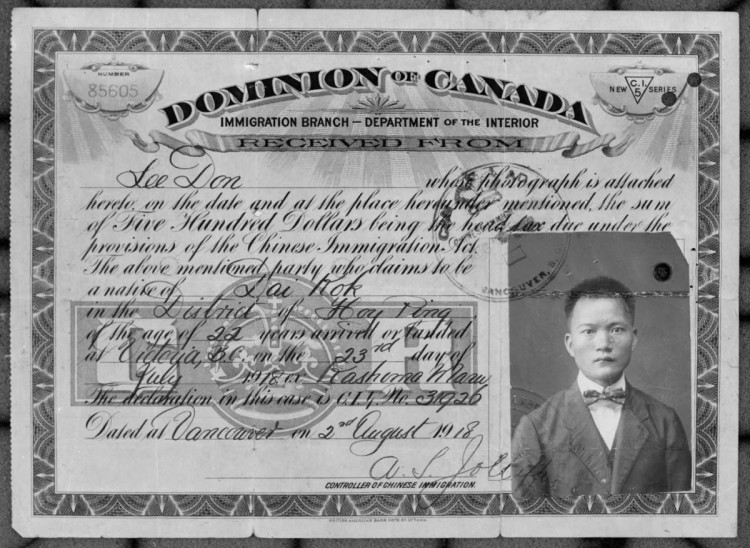

The government increased the Chinese head tax over the years. By 1903 it reached $500, the equivalent of $14,800 in 2020 dollars. And still the Chinese workers came. Parliament passed the Chinese Immigration Act of 1923, which became known as the Chinese Exclusion Act, banning almost all Chinese immigration. The Act stunted a generation’s worth of growth until it was finally repealed in 1947.

Lee Don, 22, arrived in Victoria, BC on July 23, 1918 and was forced to pay the Chinese head tax. PHOTOGRAPH: VANCOUVER PUBLIC LIBRARY/VPL30625

After the completion of the railway, thousands of workers moved east of the Rockies, while another thousand returned to China. The rest formed small Chinatowns in Victoria, Vancouver, the Fraser Valley and the Lower Mainland area. They took whatever jobs were available and were paid far less than their white counterparts.

The 1882-1883 British Columbia Directory shows that it was Indigenous workers and Chinese workers, the country’s original inhabitants and its newcomers, who belonged to the lowest category of wage earners. Indigenous workers made a daily wage of $1 to $1.50 and Chinese workers $1 to $1.25, while white workers made $2 to $3.75.

Trade unions at the time were of course, a microcosm of the larger society, and many union members deemed Chinese workers a threat — “the yellow peril.” Asian Canadian workers in the lumber sector and others were barred from joining unions. The trajectory they took to build their collective voice through workplace struggles is similar to that of the Black porters working for the Canadian National Railway, who, in 1918, had to found their own union because of the whites-only membership policy of the Canadian Brotherhood of Railroad Employees.

The Strike Against the Poll Tax

BC passed the Chinese Tax Act on September 2, 1878. For the right to stay and work in the province, any Chinese resident over 12 years old was forced to pay a $10 poll tax (or “licence fee”) every three months. Employers were required to provide a list of the Chinese workers in their workplaces and could be fined $100 if they failed to do so. The Chinese community in Victoria was enraged and immediately started mobilizing against the tax.

On September 11, 1878, the City of Victoria appointed Noah Shakespeare, an avowed racist and president of the Workingman’s Protective Association as the poll tax collector. With the police at his side, Shakespeare entered Chinatown to begin collecting. When Chinese residents refused to pay, Shakespeare retaliated by seizing their properties and belongings, and putting them up for auction.

The poll tax galvanized the community. Every Chinese business closed its doors in protest. The day after that, the entire Chinese community went on strike. Chinese workers refused to report for work at hotels, cigar-making factories and boot factories. All 200 Chinese domestic workers stayed home. No shirts were ironed, no shoes polished, no meals prepared. The strike went on for five days until, finally, the City of Victoria relented. Shakespeare was forced to resign and all confiscated goods were returned. The BC Supreme Court ruled the Chinese poll tax was unconstitutional and illegal.

The strike by these courageous “outcasts” had taken the city completely by surprise. The level of mobilizing and organizing demonstrated the cohesive force of a community that had long been ridiculed and demonized, and showed how capable it was of direct resistance against the rise of white supremacist sentiments and legislation.

Striking for Higher Pay

A Chinese worker made $225 a year at the turn of the century. While there seem to be no official earnings records for some of the common occupations, it is reasonable to speculate that the general trend of a Chinese worker’s earnings amounting to a quarter of a white worker’s would hold in sectors such as laundry, restaurant, and cigar manufacturing, where there was a high concentration of Chinese migrant workers.

They worked from 6 a.m. to midnight, seven days a week, in white-owned, newly mechanized, steam laundries, according to Paul Yee’s 2006 book, Saltwater City: An Illustrated History of the Chinese in Vancouver. Determined to change their harsh working conditions, 90 of the workers came together in May 1906 to form Sai Wah Tong, the Chinese Laundry Workers’ Union. They demanded higher wages, a 13-hour work day, a two-hour lunch break, and no work on Sundays. After successfully organizing a one-day strike in November, the workers got their monthly salary raised from $15 to $25.

Inspired by the laundry workers and their successful strike, Chinese cooks in New Westminster formed their own association in 1907 demanding a 40-per-cent wage increase. Although not as successful as the laundry workers, they did achieve a standard wage scale, as mentioned in the article “History of Chinese Migration in Canada (1858-1966).”

Between 1916 and 1920, Chinese Canadian workers began organizing to form their own unions. These included the Chinese Railroad Workers, Chinese Canadian Labour Union, Chinese Cooks’ Union, and Chinese Restaurant Workers Union. The Chinese Labour Association formed in 1916. It led strikes, mainly in the lumber industry, demanding wage and benefit parity with white workers. By 1918, the association had over 500 members.

Shingle Mill Workers Rise

In the early 1900s, Canada’s lumber industry employed large numbers of Chinese workers, paying them substantially lower wages than those paid to white workers. Chinese Canadian workers represented 70 per cent of the workforce in the lumber mills in BC, and the militancy of Chinese Canadian shingle mill workers grew over the years.

PHOTOGRAPH: Shingle workers in BC: from Saltwater City: an Illustrated History of the Chinese in Vancouver, by Paul Yee (Royal British Columbia Museum)

In Paul Yee’s Saltwater City, the author describes the working and living conditions in the shingle mills as dismal. Workers were paid according to a piecework system. Yee includes an excerpt of a 1980 interview conducted for B.C. Archives by Theresa Low with Jung Hong-len, who began working in a mill in 1915. Jung recalls:

“The mill had so many mosquitoes, you had to wrap up your face to work there. The sky would get dark, with so many mosquitoes. . . The stronger men were faster and they earned more money — 11 cents for a thousand shingle pieces. You did 10,000 and earned a dollar or so. The cutter had to work fast, so he’d find someone who could pack fast enough for him. If you cut fast, you want a fast packer. If you cut slow, you get a slow packer. . . Once you worked in the shingle mill, you always worked there, because no other work gave you as much money. Did I like it? You just had to be careful! The whites didn’t like the work, because they were afraid to lose their fingers.”

Bargaining for Equal Treatment

In 1916, Chinese shingle mill workers organized the Chinese Labour Association (CLA) and used strikes as a means to bargain for equal treatment and wage parity with white workers. The first major strike was in the sawmills of Vancouver and New Westminster, with Chinese workers pushing to shorten their working day from 10 to eight hours, in order to bring their hours in line with those of white workers.

The white woodworkers represented by the International Shingle Weavers’ Union of America began to recognize that they could not make any gains if they kept excluding their Chinese co-workers, who formed a majority in the mills. The union representing white workers approached and persuaded members of the CLA to strike for shorter working hours. A joint meeting was called on Sunday, July 17,1917, with the Chinese Times reporting it the next day as an announcement in the City News section. (Translations below of excerpts from the Chinese Times are my own.):

There was a Union meeting yesterday to discuss our demands to employers to reduce our working hours to eight hours a day. If the demand is not met, we will strike. We will hold another meeting next Sunday to make the final decision on our strike action. All Chinese mill workers please distribute the Chinese-language leaflets to your co-workers and encourage them to attend the next meeting. In order to achieve our goal, we need to know where everyone stands.

Whether you are small business operators or workers, we have all experienced harassment and discrimination from white workers. This is the first time (the white workers’ union) has contacted us to join their action. Given the fact that seven or eight of every 10 sawmill workers are Chinese, the union realizes that their actions will fail if they do not include us. So, although we know their invitation is sincere, we are also aware that the union is just being strategic and has its own motives for reaching out to Chinese workers. (July 18, 1917)

Chinese workers making barrels at Sweeney Cooperage in the early 1900s. PHOTOGRAPH: VANCOUVER PUBLC LIBRARY/VPL 3542

Well-founded Mistrust and Skepticism

So, while members of the Chinese Canadian community recognized the significance of the ‘first-contact’ gesture displayed by the Shingle Weavers Union, they felt it important to proceed with caution. Their tone of mistrust and skepticism was a direct result of the racism long inflicted on them by white-workers’ unions.

The strike began on July 23, and the Chinese Times reported:

July 24, 1917: An industry-wide strike began on July 23 as employers refused to lower working hours. A total of 2,500 white, Chinese and East Asian workers will be out on strike. This is the first time there is a united front of all mill workers. Of the 15 mills, only six are still open.

July 24, 1917 afternoon update: We have heard that the employers plan to hire white women to replace the Chinese strikers. Hiring took place last Saturday and the white women workers went in for training. But many decided not to take the backbreaking job. When asked about the impact of the strike, employers responded that they are well stocked so they are not worried.

July 25, 1917: Six more mills have re-opened as the strike continues. The employers have not hired any white women workers. Some Chinese workers who are not participating in the strike have been threatened and harassed by white workers.

On July 28, there was a final brief mention in the Chinese Times, noting that 75 per cent of the mills had resumed operation.

Even though this first strike was unsuccessful, the whole experience served to ‘inoculate’ (in our contemporary union organizing language) these strikers by giving them a sense of what to expect during a strike. It also led them, and others, to recognize the power they held as workers. In fact, the sawmill workers coming together as a united front laid the foundation for a successful strike action just one year later.

On April 13, 1918, the Chinese Times reported on that strike:

Western Canadian Mills’ Asian workers went on strike to demand a reduction of their daily working hours. After bargaining, the employer had agreed that the workers could work for nine hours and receive 10 hours’ pay. When the workers got their next pay, though, they received nine hours’ pay. This means the employer reneged on the agreement. The Chinese, Japanese and Hindu workers stood firm. The employer refused. So the workers went on strike on Tuesday. After two days, the employer relented and accepted the strikers’ demand. The workers returned to work on Thursday.

The victory and the shared understanding built among Chinese, Japanese and South Asian workers deepened solidarity and paved the way for another action: the general strike led by Chinese shingle mill workers in 1919.

As mentioned, the key issue sparking the long strike of 1919 was pay reductions targeting only those shingle workers who were Chinese, specifically those who worked as general labourers and machine operators within the industry. The employers’ differential piece rate became the lightning rod that rallied the workers and the community together and led to the success of this long strike.

On March 7, 1919, the Chinese Times reported the strike:

The sawmill employers’ scheme was to lower the wages of Chinese workers. From this month onward, machine operators will lose two cents per thousand pieces, packers one cent per thousand pieces, and general labourers, ten cents per dollar earned. All Chinese shingle workers find this unacceptable and have decided to stage a general strike. There are about 800 Chinese workers in more than 15 mills. This show of force and unified support for strike action is unprecedented in the Chinese community. The strikers have vowed that they will not return to work if the wage reduction is not withdrawn.

Chinese Times Editor’s Note: Among the Western [white] workers, there is a union for each occupation to serve as a protection. Only Chinese workers have no such organizational support. If this situation does not change, it will weaken our solidarity. Chinese workers are now being targeted by employers, but we do not have an organization to build a united force to counter and fight back. It is time for our Chinese shingle workers to reflect and decide what to do.

The Birth of a Union

The call to form a union resonated with Chinese shingle workers, and the Chinese Shingle Workers’ Union of Canada was formed. The union set up offices in Chinatown and organized the strike. The employers responded by starting a school to train war veterans to replace the Chinese workers, but the plan failed.

After 40 days of striking, the workers succeeded in recovering their original wages. With their new-found confidence, they demanded higher wages in April to compensate for the strike losses. Once again, they won. The union also advocated for, and won, higher wages for part-time workers.

In 1920, the Chinese Canadian shingle workers’ union appointed representatives to every mill. From plant to plant, workers went on strike against poor treatment and harassment.

This collective agency and organizing power among the workers in fighting for equal treatment became the pride of the community as a whole.

Worker solidarity and bargaining power began to erode as the economic downturn of 1920 took hold. By January of 1921, wages were being cut and many workers were being dismissed. The organizing base of the Chinese Shingle Workers’ Union began to evaporate. When workers struck at one factory to protest plummeting wages, desperate strikebreakers came in to take their jobs.

From 1919 to 1921, some Chinese Canadian workers joined the One Big Union (OBU). They recognized that uniting with fellow workers would increase the chance of success for all. Under the united front, Chinese and white workers marched and organized strikes to advocate for wage increases and reduced work hours. They also began to take a firm stand against racist abuses perpetrated by white supervisors.

Even though the 1923 Chinese Exclusion Act profoundly affected the growth of the community, Chinese Canadian workers continued to engage in the broader labour movement, asserting their presence and standing up against discrimination.

Unemployed Chinese Workers Protest

Chinese labourers were hit hard during the Great Depression. Roughly 80 per cent of the residents of Vancouver Chinatown were unemployed. The provincial government set up the Anglican Chinese Mission to provide shelter and two daily meals for unemployed Chinese Canadians. But even within this relief program, treatment was differential. Unemployed Chinese workers were fed on a formula of eight cents per meal, while white workers were allotted 15 to 25 cents per meal. Over a period of three years, at least 145 unemployed Chinese workers in Vancouver died of malnutrition.

May Day in Vancouver, 1935. PHOTOGRAPH: VANCOUVER PUBLIC LIBRARY/VPL 8799

The workers formed the Chinese Unemployed Workers Protection Association, protesting racist government practice and demanding equal benefits and treatment for all unemployed workers. Members of the association marched alongside unemployed white workers on May Day in 1935, demanding that the government shut down the soup kitchen run by the Anglican Church.

The Chinese Times reported extensively on the march the next day:

May 2, 1935: Yesterday, May Day was a festive celebration for the Communist Party. Party members, trade unionists, and high-school and elementary-school children marched from Cambie Street to Stanley Park. There were over 14,000 marchers including strikers and unemployed workers singing and shouting slogans, and holding up traffic for over 40 minutes. There were 1,200 school children present along with members of different unions . . . Members of the Chinese Unemployed Workers Association were also there with their banner, which reads: “145 Chinese Workers Killed by Soup Kitchen, Starved by Anglican Church on Contract.” There were also Japanese workers present holding a banner, “Stop the Sale of Scrap Metal to Japan!” The parade went on until late afternoon.

Marching and working together for common demands and union principles led white workers to respect and better understand Chinese workers, whose organizing and militancy as union activists effectively turned some anti-Asian union members into allies.

The Visionary Roy Mah

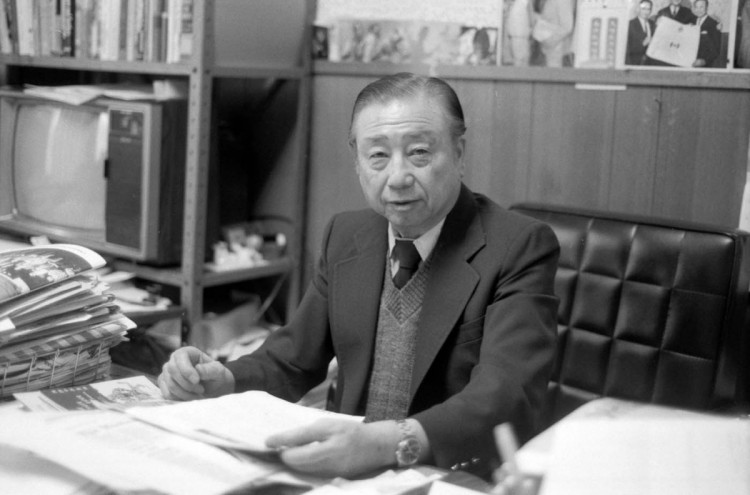

It is impossible to write about the early militancy of Chinese Canadian labour activists without acknowledging the contributions of Roy Mah. In 1944, Mah became the first full-time Chinese Canadian union organizer hired by the International Woodworkers of America, (which merged with the United Steelworkers in 2004). The IWA also recruited Japanese and South Asian union organizers to reach out to the diverse workforce in the sawmills.

Labour activist and journalist Roy Mah was a visionary who recognized the importance of communicating with potential union members in their own language. PHOTOGRAPH: PAUL YEE

Mah was a visionary. He recognized the importance of communicating with potential members in their own language. He put out a Cantonese edition of the union’s newsletter, the first ever in North America. After serving in the war for a country that denied him the vote, he returned to the IWA for two more years. He is credited with bringing as many as 2,500 Chinese Canadian sawmill workers into the union, according to Rod Mickleburgh’s On the Line: A History of the British Columbia Labour Movement.

Mah, as a war veteran, was influential and instrumental in organizing the campaign which saw both the Chinese Exclusion Act repealed and Chinese Canadians enfranchised in 1947. He went on to become the publisher of Chinatown News, Canada’s first English-language Chinese Canadian magazine. Published biweekly from 1953 to 1996, it connected members of the Chinese Canadian community to one another, and served as a bridge to the larger society.

Reflections and Lessons

Through this excavation project, I have been deeply moved by the tenacity and militancy of early Chinese workers in Canada. I am also amazed by how firmly their community stood by them.

In the face of exclusion and discrimination, Chinese Canadian workers organized and became proud members of their own unions. Far from being victims, they founded a labour movement. These early immigrants used petitions, strikes and boycotts to fight for their basic rights, challenging the stereotype of Chinese Canadian workers as submissive and obedient. Their resistance and militancy shattered the other widely held notion of Chinese workers as strike-breakers, and enemies of organized labour. As Edgar Wickberg in his 1982 book, From China to Canada, so aptly points out, “They were prepared, where feasible, to resist being made the scapegoats, and to do so they organized unions when they could.”

Of the view that Chinese workers were either passive or strikebreakers, Wickberg says, “An awareness of the militancy of Chinese activity during the 1911-1923 period should revise that view. Militancy is not a new development in the Canadian Chinese community in 1911.”

They so successfully organized, in part, because organizers and leaders of these early unions shared not only the same language but also the experiences of being discriminated against and exploited on the shop floor. These workers were what Jane McAlevey in her book No Shortcuts (2016) refers to as the organic leaders — the ones who come from within and who have already secured the respect and trust of their fellow workers. These courageous leaders in turn took direction from those who were most affected and harnessed their anger into action.

These organic leaders were also the ones who sustained the continuous organizing in the mills despite the initial setbacks. They drew lessons from the strike of 1917 for an eight-hour work day, and they kept up workplace activism and built momentum for the strike action two years later.

Driven by righteous anger over racial injustices and exclusion, their activism was also grounded in class-consciousness . Race sharpens class: Applying the lens of race complicates the narrative and leads to a more nuanced discussion of working-class struggles. The intersections of race and class became a potent and powerful force for labour militancy.

As Toni Morrison, in a 2015 interview with the CBC, put it with stunning clarity, “Racism pays . . . They have done it throughout history — identifying who that enemy is and who benefits from that distinction.” She goes on to say, “Racism costs the raced and it benefits and profits the people who established the other. It always has.”

In their collective desire to be made whole, workers have always fought for fairness, respect and dignity.

Chinese Canadians have a history of labour militancy. In 2011. 140 workers at Ming Pao Daily, in Toronto, went on strike for 73 days to win their first collective agreement (Winne Ng, centre front). PHOTOGRAPH: JOHN MACLENNAN

The same militancy and commitment to justice has prevailed for over a century now. In the 2000s, we saw organizing campaigns led by the Chinese Canadian workers at Toronto-based Singtao Daily Newspaper and the Toronto location of the Ming Pao Daily. After successfully joining the Communications, Energy and Paperworks Union of Canada’s (CEP) Local 87M Southern Ontario Newsmedia Guild (SONG), now Unifor Local 87M (SONG), both groups ended up on strike for their first collective agreements — Singtao Daily workers in 2001 for 43 days. Ten years later, 140 workers from the Ming Pao Daily struck for 73 days.

One cannot but marvel at the foresight of the IWA in recruiting staff organizers with diverse linguistic and cultural backgrounds, at the publishing of union newsletters in languages other than English, and at the leadership of Roy Mah. Nelson Mandela once said, “If you speak to someone in a language that he understands, it goes to his head. But if you speak to someone in his own language, it goes to his heart.”

Union organizing is indeed a matter of the heart. It needs constant nurturing and support to fully bloom. If a strategy of actively recruiting diverse and multilingual full-time organizers had been deployed, and sustained, in every union across the country these past decades, how profoundly different the union membership would look, and how rich our labour movement could be.

When I wrote this article in March 2020, the world was a very different place. We are now in unsettling and unprecedented times. COVID-19 has exposed and exacerbated the inequalities of a system driven by greed, profit and unfettered power.

The massive Black Lives Matter protests across the globe, triggered by the cold, callous murder of George Floyd in May, have more fully revealed the insidious pandemic of anti-Black racism. Our collective power and responses during this time of reckoning are required to wrestle this beast.

COVID-19 has also unleashed a surge of anti-Asian racism across the country. Incidents have included racist name-calling, assaults and even the violent attack of a 92-year old Chinese senior citizen in Vancouver. These are acts of white supremacy that unmask the North American façade of Asians as a “model minority.” No matter how hard we try to “assimilate” or “blend in” we are rudely awakened to the reality that we can be considered “perpetual foreigners” in an instant.

We must circle back to the question posed in the beginning of this article: who are considered the real Canadians, and therefore, the real workers? The pandemic has unmasked politeness and pretence, and shown that the colonial narrative of the “founding of Canada” is always simmering just beneath the surface.

Indigenous, Black and other people of colour are being manipulated into competing with each other for crumbs. It’s important that we fully endorse the battle cry of Black Lives Matter Toronto: there is no Black liberation without Indigenous sovereignty.

As Asian Canadian labour activists, it is critical that we reflect on a number of questions:

• How are we complicit in Anti-Black racism and anti-Indigenous racism?

• How do we unlearn and challenge anti-Black racism and anti-Indigenous racism?

• How do we move beyond the notion of ”being an ally” and take up Sister Carol Wall’s call to become ”co-conspirators” in the dismantling of white supremacy? (For more, read Carol Wall’s open letter to white sisters and brothers, featured in the Summer 2020 issue of Our Times.)

Finally, how do we get this message across within our diverse communities: A system that addresses white supremacy head-on is a system that will benefit us all.

In answer to all of these questions, we can start by learning the real history of Canada.

Unearthing stories of resistance about our diverse BIPOC communities and telling them with all the richness of our own voices are indeed acts of disruption, occupation and reclamation!

Winnie Ng is a long-time labour-rights activist, educator, and community organizer with a deep commitment to anti-racism, equity and worker empowerment. She served as the Unifor-Sam Gindin Chair in Social Justice and Democracy at Ryerson University from 2011-2016. She is currently an adjunct professor with Ryerson’s School of Social Work.